“How many of you have had to fill out a web form after being asked to read a distorted sequence of characters like this? … How many of you found it really, really annoying? … I invented that!”

Luis von Ahn, inventor of captchas and computer science professor at Carnegie Mellon University, always gets a laugh with those lines at the start of his talks, and so he did at the Surge conference in Bangalore last week.

But the captchas – which confirm users are humans and not robots – are only an ice-breaker for talking about his current passion. Luis is the co-founder and CEO of Duolingo, a free language learning app with 110 million users worldwide. It’s the most downloaded app in the education category on both Google Play Store and iTunes.

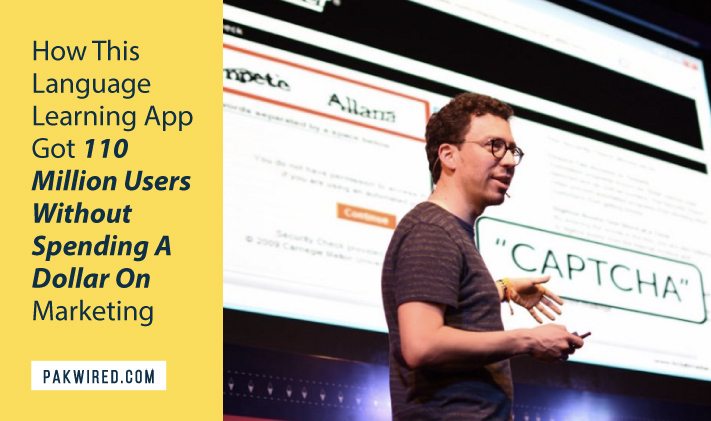

Duolingo uses a task-based, gamified, multiple choice format to get you up to speed on using a language. If you’re an English speaker, you can choose from 16 other European languages to learn currently – that is, Spanish, French, German, etc. For a Hindi speaker from India, it uses Hindi to teach English. At a very basic level, that involves asking questions in Hindi and getting the user to pick the right translation in English by looking at pictures, as you can see in this screenshot.

It gets more interesting as you progress in the course. Machine learning at the back-end automatically adjusts the difficulty level depending on your performance in the lessons which range from listening and speaking to multiple choice tests. A study claims 34 hours spent on Duolingo by the average user is equivalent to a university semester of language education.

Although Duolingo does not yet teach Asian languages to English speakers, it teaches English to speakers of Hindi, Mandarin, Japanese, and most Asian languages. The priorities are based on demand and RoI (return on investment) – Spanish, for example, is the most popular choice for English-speakers wanting to learn a foreign language.

How to keep users engaged

The world’s richest man, Bill Gates, was a Duolingo user, albeit briefly. He confessed on aReddit AMA that he “feels stupid” for being monolingual, and envies Mark Zuckerberg for being able to talk to the Chinese in Mandarin.

“I wish I knew French or Arabic or Chinese. I keep hoping to get time to study one of these – probably French because it is the easiest. I did Duolingo for awhile but didn’t keep it up,” Bill Gates regretted.

That he chose Duolingo gave the app a big boost. But the other side of the coin is that he dropped out too. That is the biggest challenge for learning apps, and most edtech startups for that matter: the alarming dropoff rates.

So how did Duolingo get up to 110 million users within three years of launching? What’s the secret to keeping so many users engaged? Those are the questions I posed to Luis, who was part of a panel I moderated at Surge on what learning companies can teach us about retaining users.

Lessons from Candy Crush and the casino

“Learning is like going to the gym,” explained Luis. It has to be fun to make you want to go and work out everyday. That’s what Duolingo tries to do with its gamification.

Luis’ favorite tweet is from a user who said he had stopped playing Candy Crush and started doing Duolingo. So what’s the connection between Candy Crush and Duolingo?

Well, they both reached very large scale quickly. But Luis reveals another secret connection – Candy Crush uses machine learning to figure out how many candies to have in a row on top to keep the gamer hooked. It uses the same tactic as a casino, where a slot machine increases your chances of winning on the first couple of tries to give your brain a dopamine rush to go for more.

Duolingo uses similar psychology to hook users. It has a progress bar on top which expands or shrinks depending on how you do on multiple choice challenges. This is rigged to keep you hooked with more positive reinforcement than you’ve probably earned in the early stages.

Disrupting the English testing and certification industry

Photo credit: Pixabay.

Interestingly, Duolingo used to have a row of hearts where it now has a progress bar. Each time you got something wrong, a heart dropped off. If you lost all the hearts, you had to start all over again.

The shift to the progress bar was initially an experiment based on a feeling that users were literally losing heart when they say the heart icons fall off. The machine learning data, which Duolingo relies on heavily, confirmed the hypothesis – there was indeed more engagement with this simple tweak to the user interface.

Engagement also comes from the basic premise of Duolingo which is that learning by doing is more effective. So users learn by translating words and sentences with pictorial or other cues.

Luis claims the effectiveness of these methods accounts for the popularity of Duolingo. “We didn’t spend a single dollar on marketing,” he says. Awareness spread by word of mouth, such as that of Bill Gates, even though he later dropped off.

The vision that Luis has of making language learning available all over the world to all sections of society, and not just the well-off, appeals to many. Duolingo is now working with public schools in several countries, including the US, to make it a practical part of language education. So, both its mission and the effectiveness of its teaching modus operandi have made the app popular.

Luis and his investors – among whom is the actor Ashton Kutcher – remain committed to keeping the app free for users and without ads. One of the ways it makes money is the option to take a test to certify proficiency in English or any of the other languages on the app. Users take the test online through live video to ensure they’re doing it themselves.

This year 12 premier universities in the US will run an experiment to compare Duolingo English tests with those of traditional tests like TOEFL and ESL for their applicants. The idea is to see whether to accept Duolingo test certificates as an alternative to those like TOEFL which are ten times more expensive and much less convenient.

The size of this market is huge. In China alone, points out Luis, there are 400 million people learning English who require some form of certification to prove their proficiency for a job or studies abroad. So testing and certification for English is a massive and inefficient industry that Duolingo hopes to disrupt.

Luis lived in Guatemala – “not Guantanamo,” he likes to quip – before moving to the US as a student. He had to go to neighboring El Salvador to take his TOEFL because none of the testing centers in Guatemala could accommodate him in time. The travel cost him a packet apart from the test fees. “This is technology from like a hundred years ago,” – that’s how he sees the testing and certification scene.

Duolingo is also working with companies, including Uber, to provide English learning and testing. Uber, for instance, wants to provide drivers who can speak in English.

Prof who sold his startup to Google

Photo credit: Surge conference.

Luis’s obsession with using tech to deal with language predates Duolingo. As we’ve already mentioned, he invented captchas. That was some 15 years ago and it caught on all over the web. But then, the professor’s computer brain started ticking and left him with a feeling of guilt.

He worked out that it takes 10 seconds for somebody to type out a captcha, and 200 million of these are typed out everyday – “humanity as a whole was wasting 500,000 hours everyday in typing out these annoying captchas.”

That’s how he came up with his next project ReCaptcha. The idea here was to crowdsource the digitization of books, which would be a service to humanity rather than the pain that captchas had become.

Computers use OCR (optical character recognition) to convert scanned images of the pages of a book into digital formats. The problem is that OCR doesn’t work well with the old, frayed, yellowing pages of many of the books being digitized by Internet Archive, Google Books, and others.

Luis’s solution was to break up this problem into teensy-weensy bits. ReCaptcha presents two squiggly words in web forms that people fill to show they are humans and not bots. One of the words you type is the test word that the computer checks against the correct result. The other one – and you don’t know which one – is actually a word from a book which you unknowingly help to digitize by typing it into the web form.

Soon a large number of sites, including Facebook and Twitter, switched from the old captcha to recaptcha. Each day 100 million words from books were being digitized, which added up to two-and-a-half million books in a year.

Luis then sold ReCaptcha to Google and began toying with the idea of Duolingo because he wanted to “do something in education that would be good for humanity.”

Machine learning at its core

One of his PhD students at Carnegie Mellon, Severin Hacker – yes, that’s his real name – joined Luis in this new project. The initial assumption was that they only had to look at the best language learning books and other resources to develop the app. But they soon ran into a problem – there was little agreement among academics on the most effective methods for learning a second language.

Being engineers, Luis and Severin decided to build in machine learning to figure out from users themselves how they learned best. Should you learn verbs before adjectives? When should you move from learning words to composing sentences? How do you graduate to more complex sentences and dialogue? And so on.

This has now become the mainstay of Duolingo – not only for the effectiveness of its language learning methodology but also in user engagement. It’s a constant process of experimenting with different users and situations and cultures to see what works and what doesn’t. That’s how it crossed the 100 million user mark.

This post was originally published on: techinasia.