THE first thing to come back was the prime minister. Having twice held Pakistan’s highest office before the army toppled him in 1999, Nawaz Sharif returned from exile to win it back in 2013. This was a personal triumph but also a historic moment, marking the only time since Pakistan’s founding that one elected government has completed its term and passed power to another. It also turned out to be the first of a heartening series of signs that Pakistan itself seems to be returning, slowly and haltingly, to a more stable and prosperous state.

For the eight years since terrorists attacked a visiting Sri Lankan team, Pakistan’s cricket-mad citizens have forfeited the joy of watching top international matches on Pakistani soil. But on March 5th Lahore, the capital of the province of Punjab and site of the attack in 2009, hosted the final match of the Pakistan Super League, a lucrative franchise with many foreign players. For safety reasons the PSL’s matches had until now, embarrassingly, been staged in the United Arab Emirates. In February Pakistan also held its first international skiing competition since 2007, when Taliban militants overran its biggest ski resort, at Malam Jabba in the Swat Valley, and smashed the “heathen” lifts.

More broadly indicative is that Pakistan’s stock market has risen faster than any other in Asia over the past 12 months, by a heady 50%. Perhaps this is because annual GDP growth, having languished below 4% from 2008 until 2013, is now back to the long-term average of around 5%. Poverty has fallen and the urban middle class is growing. Nestlé, a giant maker of processed foods, says its sales in Pakistan have doubled in the past five years, to over $1bn.

Across much of the country, too, lights are coming on again. When Mr Sharif resumed office four years ago Pakistanis rarely enjoyed more than 12 hours of electricity a day. “It was so acute that private backup generators could not recharge the batteries that start them up,” says Ahsan Iqbal, the minister of planning. Big investments in power infrastructure mean that power cuts are now down to a more manageable 6-8 hours a day. The government hopes to eliminate them entirely in time for national elections next year.

That deadline has prompted another important step: over the next two months Pakistan is due to hold its first national census since 1998. Some 90,000 civilians and 200,000 soldiers are being mobilised to count the country’s 200m-odd inhabitants. The results will be used, among other useful things, to reapportion parliamentary districts. Until a recent revision, Pakistan’s constitution stipulated that a census should be taken every ten years. The fact that there have been only two in the past 45 years says much about the tragic drift under both military and civilian rulers.

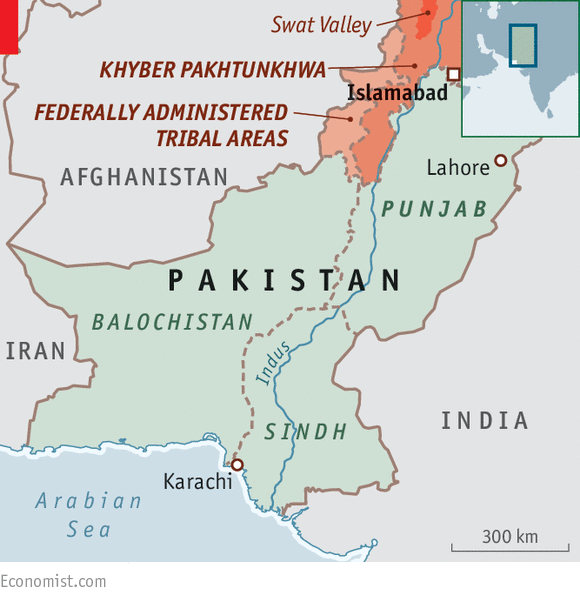

Of anywhere in Pakistan, the part that may have got the shortest shrift is the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA). British imperialists regarded this rugged region along the Afghan border as so untameable that its tribal chieftains were left to impose their own laws, a dispensation that has continued to this day. One result is backwardness: in one district the proportion of girls enrolled in school in 2011 was a shocking 1%. Across FATA as a whole, female literacy in 2014 was estimated at just 13%. This contrasts with national literacy rates of 43% for women and 70% for men.

Another result has been insecurity. The endless war in Afghanistan flooded FATA with guns, refugees and radicalism, all of which Pakistan’s armed services unwisely sought to harness in pursuit of their own murky agenda, both in Afghanistan and at home. Having slipped completely out of control in the late 2000s, FATA has been pacified in recent years only by a mix of American drone strikes and Pakistani offensives on the ground. As many as a third of the region’s 4.5m people are believed to have fled. A government report in 2016 estimated that military operations over the previous decade had destroyed 67,000 houses and left 27,000 dead.

Given all this, the government’s recent announcement that it plans to normalise the administration of FATA is welcome. It will be absorbed into the neighbouring province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, giving it elected leaders rather than tribal elders, regular courts that apply national laws and ordinary police instead of tribal militias. Locals seem pleased: a recent survey found hefty majorities backing all these changes.

Despite all the good news, however, Pakistan’s progress remains unsure. Terrorist attacks, bombings, murders, kidnappings and brutal state retaliation continue at a brisk pace. Pakistan’s powerful military remains dominant and its secret services opaque. Take the case of the vanishing bloggers. Over three days in January, five obscure social-media commentators who had dared to criticise the army vanished from different parts of Punjab. The army denied any involvement, but pro-military social media sites were quick to label the abductees blasphemers, apostates and traitors—in a country where blasphemy remains punishable by death. “Their crimes are so heinous that no one should say…that they suffered injustice,” tweeted one notoriously craven television host. Four of the men were eventually released, but have refused to talk about their ordeals.

Some Pakistanis question how much has really changed. Commenting on the elaborate security for the PSL final, Anjum Altaf, a columnist for the Dawn newspaper, harrumphed: “I fail to understand how spending hundreds of thousands of dollars to bribe a handful of foreigners to play a game in a nuclear bunker can be convincing proof that the country is back to normal…This is self-delusion carried to absurdity.” For Pakistan, however, even to be debating the subject is encouraging.

This post was originally published on: Economist.